Benin President Patrice Talon (Photo: Présidence de la République du Bénin)

Benin’s April 11 presidential election was a quiet affair. There was little media attention or sensational developments. Indeed, the outcome was a foregone conclusion following President Patrice Talon’s effective barring of serious competitors. The resulting boycott led to an estimated 26-percent voter turnout. The polls were both literally and figuratively quiet.

Also muted were any objections from regional actors. A team of 16 African Union observers concluded with approval that the election was “calm” and “took place in a peaceful atmosphere.” Remarking on the absence of queues and voters, they recommended education campaigns to increase future turnout. The observers encouraged the government to continue promoting “a climate of calm and serenity” in future electoral processes. An Economic Community of West African States team of 105 observers congratulated Benin and its political leadership on an “orderly” election, even though its report noted that a “low turnout of voters was observed from the early hours of the polls.”

The Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) reported that the election “took place in accordance with the legal framework in force, and in a calm manner over most of the territory.” OIF’s preliminary report included a brief mention of the one-sided organization of the election as contributing to the limited participation.

“The silence in the aftermath of Benin’s election is deafening and surely being noticed by other would-be autocrats.”

These omissions, congratulations, and encouragements were offered despite a multiyear process of Talon taking control of the parliament by preventing opposition parties from competing, coopting the judiciary, politicizing the security sector, and intimidating the media.

These events have shown that democracy does not only die with a bang at the hands of coup leaders but that it can be swiftly and silently legislated into a skeleton of its former self absent a joint domestic and international effort to block such an outcome. The consequences in Benin’s case are particularly painful given that the country was not long ago a proud beacon of democracy globally.

The silence in the aftermath of Benin’s election is deafening and surely being noticed by other would-be autocrats on the continent. If this is the standard for an acceptable election, then there promises to be more of such quiet elections in the future.

The quiet in Benin will only last so long, however. Illegitimacy and autocracy are often accompanied by instability. Widening disparities, corruption, the drying up of investment, and the further deterioration of the rule of law are all precursors to further abuses of power, economic crisis, and conflict.

A Systematic Weakening of Benin’s Democratic Institutions

The list of legal gambits employed by Talon and his loyalists to normalize political exclusion is long and intricate.

Benin National Assembly. (Photo: VOA/Ginette Fleure Adandé)

In the run-up to the 2019 legislative elections, the Talon-appointed electoral commission invalidated the candidacy of all but pro-Talon parties based on last-minute registration requirements. Once in office, the new Talon-dominated National Assembly rubber-stamped a new electoral law requiring candidates to receive sponsorships from sitting officials. In effect, the new requirement gave the ruling party veto power over any candidate’s ability to run for office.

The African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), the regional court established by the African Union to provide recourse to citizens when justice is not possible within their own countries, has repeatedly ruled that Benin’s constitutional revisions and other antidemocratic actions violate the African Union’s African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance. It found that the constitutional revisions that created the sponsorship system were rushed through the National Assembly without consulting the people of Benin in violation of the country’s 1990 Constitution.

Rather than repealing the unconstitutional laws before the 2021 vote as ordered by the court, Talon’s response was to withdraw Benin’s membership from ACHPR.

Headed by Talon’s former personal lawyer, Joseph Djogbenou, Benin’s own Constitutional Court has repeatedly ruled in Talon’s favor. This includes matters in which Djogbenou was formerly involved as the Minister of Justice, blurring the responsibilities of the executive and judiciary.

Joseph Djogbenou (Photo: Présidence de la République du Bénin)

One of Djogbenou’s initiatives from his time as Minister of Justice—a special court to prosecute terrorism and economic crimes (CRIET)—has been used to quash dissent over the election results relying on a special police unit, the Brigade économique and financière. A week before the 2021 election, a CRIET judge resigned and fled the country citing political instructions to prosecute Talon opponents, such as Reckya Madougou, who had led civil society opposition to Talon’s constitutional changes and was the presidential nominee of the Democrats political party. (Her candidacy was invalidated along with all but two lesser-known candidates).

Facing no consequences from this judge’s defection and revelations, CRIET had another opposition candidate, Joël Aïvo, arrested days after the election. He had announced his decision to boycott the election on Facebook. Human rights organizations in Benin are now raising the alarm over a massive wave of arbitrary arrests of members of civil society who have been marched in front of CRIET in the leadup to and aftermath of the election. Talon’s government has said that these arrests represent “the end of impunity” in the country. In practice, it appears to signal the end of freedom of expression.

The ability of Benin’s domestic media to cover these events and politics more generally has been curtailed by the passing of media laws that criminalize the criticizing of government officials. Amnesty International has documented 17 instances of journalists and activists being detained under Benin’s new Digital Code, which makes it a crime to publish information online deemed by the government to be harassing or false. This has had a chilling effect on domestic media . Information on what is happening in Benin is often now passed through exiles living abroad or foreign correspondents. Under Talon, Benin has dropped from number 78 to 114 in Reporters without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index.

“The question of political legitimacy … overshadows everything done by the Talon administration.”

Arbitrary arrests of journalists and civil society members have been carried out by increasingly politicized elements of the security sector. The ACHPR ruled that Benin’s security forces violated citizens’ human rights in 2019 by using live ammunition on protesters. Instead of being brought to justice, all involved were given amnesty by the newly elected National Assembly. In the leadup to the 2021 election, ad hoc army units directed by the president’s military advisor fired on protesters, killing at least two people. Talon praised their response as showing “great skill and expertise.”

In short, these and other systematic maneuvers by the Talon government have picked apart Benin’s democratic organs until its citizens saw no choice but to sit out the pre-ordained 2021 election in protest.

The question of political legitimacy, thus, overshadows everything done by the Talon administration. An election in which three-quarters of voters do not go to the polls out of protest is a powerful indictment. Recognizing this, the Talon government has claimed a 50 percent turnout for the 2021 vote, though has failed to release results by precinct. The independent Electoral Platform of Civil Society Organizations in Benin deployed 1,281 observers on election day and tallied the 26 percent turnout figure while noting that “in all departments [of the country], attempts at pressure, intimidation, threats, disturbances of public order, corruption or harassment of voters were observed.” A number of polling stations never opened on the day of the election, a reality acknowledged by the electoral commission.

A Crisis of Legitimacy That Threatens Stability

Democracy is not only a governance vehicle for freedom, equality, and human rights, but it is also a means of advancing national security—domestically and internationally.

The ACPHR’s rulings make clear that Benin’s new electoral rules “break the social pact and raise fears of a real threat to peace in Benin.” Benin’s reputation for being a shining multiparty democracy has gone hand-in-hand with its reputation for stability and social cohesion since the enactment of its landmark Constitution in 1991. The crisis of legitimacy that Talon has created runs the risk of politically marginalizing citizens and of cutting off avenues for peaceful dialogue and democratic change.

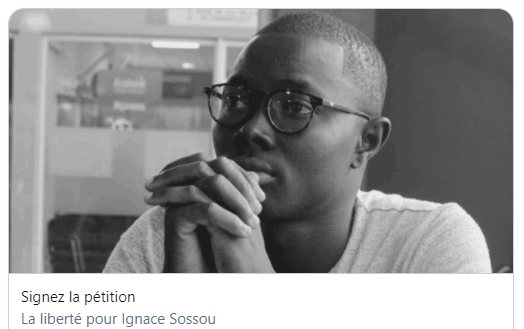

Screenshot of an online petition for Ignace Soussou’s freedom.

While Benin has witnessed economic growth during Talon’s tenure, those gains have largely benefited elite interests like Talon’s cotton holdings (which have made him one of the richest people in Francophone Africa). Moreover, credit analysts have warned that Benin’s rising political instability may reverse its economic gains. Under Talon, workers in several public sectors have been banned from striking by Djogbenou’s Constitutional Court after protests over unpaid wages and working conditions in 2018. Rather than prosecuting corruption, courts in Benin have recently prosecuted investigative journalists, including Ignace Sossou, who was part of the Panama Papers investigation with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Militant Islamist groups operating in the Sahel have targeted Benin’s north for expansion. The largely Muslim north has been politically marginalized under Talon, creating disaffection—especially among youth, 39 percent of whom live in poverty amid high youth unemployment—that militant recruiters in neighboring Niger and North West Nigeria have sought to exploit. Experience from elsewhere has shown that hollowed out security forces focused on attacking domestic political opponents are not very effective at defending a country’s borders. Benin’s growing autocracy and estrangement of its citizens, thus, leaves it especially vulnerable to the risk of violent extremism spilling over from the Sahel.

Reversing the Downward Spiral

A depiction of the serpent deity, Dangbe, of whom shrines are still found in Benin, consuming its own tail.

Beninois continue to resist the loss of their democratic rights through appeals to the courts, boycotts, and protests. These have come with costs. At least 400 have been arrested and others have gone into exile. Protests following the 2021 elections were met with live ammunition by ad hoc army units, killing at least two people. Talon praised the security forces’ response, denying that any demonstrators were killed, while dismissing the protestors as “manipulated children.”

Having neutralized domestic democratic checks and balances, Talon is only likely to consider reversing course if he faces tangible political and economic costs. Conversely, autocratic leaders who learn they can usurp power and undermine the rule of law tend not to do so just once. Rather, these actions become part of a pattern of abuse of power. Talon has already backtracked on his promise to serve only one term and is likely to argue that his constitutional revisions reset his term limits.

Re-legitimizing Benin’s democracy will require the international democratic community calling out the hollowness of the recent election. An election in which no one shows up, after all, will always be “calm and orderly.” That does not make it legitimate. Reversing Benin’s self-inflicted spiral toward instability and autocracy will require more than words of admonishment. It will require sanctions, the withholding of foreign assistance, and the discouragement of investment.

External actors are also needed to more forcefully demand that Talon’s government engage the opposition in dialogue and create real space for citizen participation. A truly inclusive national dialogue (a “political dialogue” in 2019 excluded the opposition) and the release of demonstrators and political prisoners would be a good place to start.

Additional Resources

- Juste Codjo, “Bénin: Que faire pour prévenir des épisodes d’instabilité,” Hémicyles D’Afrique, March 14, 2021

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Autocracy and Instability,” Infographic, March 9, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Spike in Militant Islamist Violence in Africa Underscores Shifting Security Landscape,” Infographic, January 29, 2021.

- Joseph Siegle and Candace Cook, “Taking Stock of Africa’s 2021 Elections,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 12, 2021.

- Daniel Eizenga and Wendy Williams, “The Puzzle of JNIM and Militant Islamist Groups in the Sahel,” Africa Security Brief No. 38, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 2020.

- Joseph Siegle and Candace Cook, “Circumvention of Term Limits Weakens Governance in Africa,” Infographic, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 14, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “ECOWAS Risks Its Hard-Won Reputation,” Spotlight, March 6, 2020.

- Mark Duerksen, “The Testing of Benin’s Democracy,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 29, 2019.

More on: Benin Governance